Irresistible by Adam Alter

First, please don’t worry if the paperback cover and subtitle are different to the illustration. The publishers will have a reason for changing the subtitle to “Why you are addicted to technology and how to set yourself free” – but the contents of the book appear to be identical. “Irresistible” is more about diagnosis than self-help. It is a book that I think deserves to be widely read – and happily it isn’t a difficult read.

Adam Alter is a psychologist and writer, currently based at New York University’s Stern School of Business. His academic research focuses on social psychology, judgment and decision-making, with an interest in the effects that subtle cues in the environment can have on human cognition and behaviour.

‘Irresistible’ is broken into three sections:

1. a review of ‘behavioural addiction’;

2. the ingredients of behavioural addiction; and

3. the future (including some solutions).

The prologue - “Never get high on your own supply”, showcases the unwillingness of the Big Tech leaders to expose their children, when young, to their own products. Tristan Harris (founder of the Center for Humane Technology) appears as well, “the problem isn’t that people lack willpower; it’s that there are a thousand people on the other side of the screen whose job is to break down the self-regulation you have.” Alter concludes the prologue with hope. “The good news is that our relationships with behavioural addiction aren’t fixed”, he sees much we can still do to restore balance.

‘Irresistible’ begins with the challenge – most of us (over 88% of one sample) are spending more than 1hr/day using our phones – many spending as much as a quarter of our waking hours interacting with it. Even the visible presence of a smart phone in a room seems to undermine our attempts to interact with other human beings. Adam Alter takes us on a journey through gaming (a useful forerunner of the smart phone – when it comes to relevant research) to understand where the notion of behavioural addiction has come from. He runs through internet and smartphone addiction and provides a short history of different forms of substance addiction.

There is a long-running controversy amongst medics and mental health professionals as to whether it is possible to be addicted to an activity rather than a substance. Alter is convinced that behaviour addiction – carefully defined, is a real problem. He offers an engaging story by combining history (including the American Civil War and the Vietnam war) and some interesting research. Alter argues that we all have the potential to be addicted – the mechanisms of the human body are prone to it, if stimulated in the wrong way.

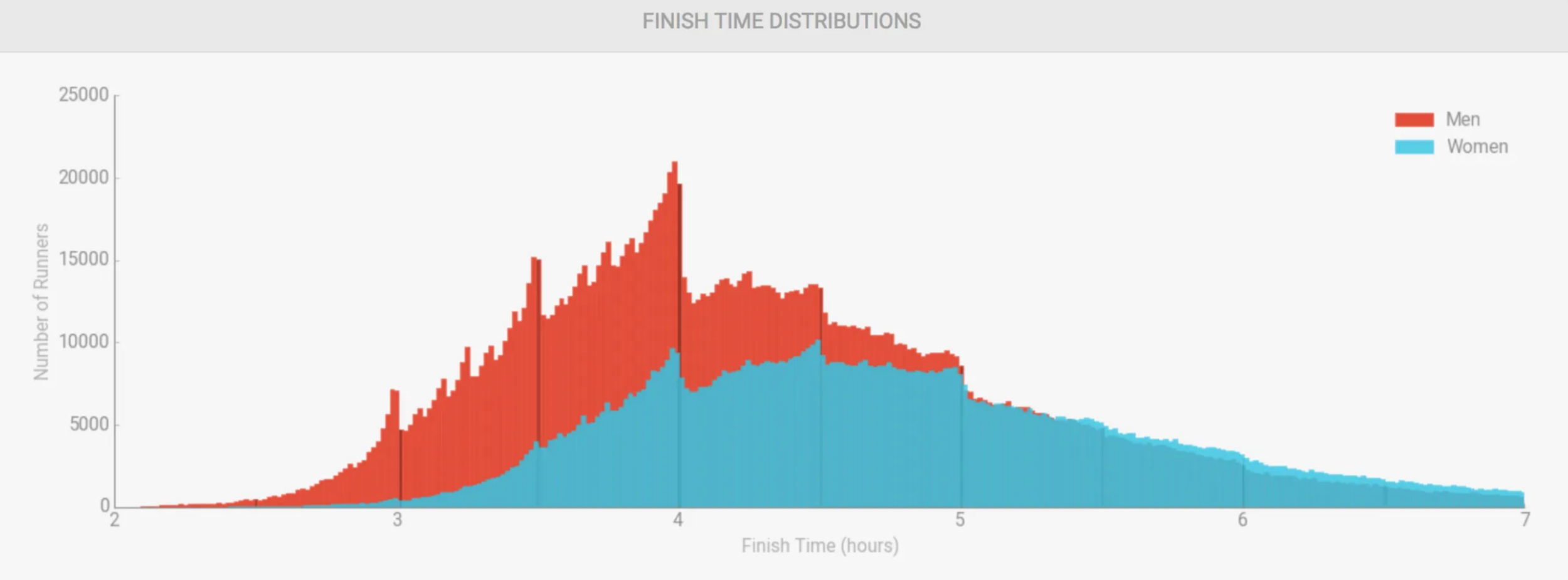

Marathon times showing clear peaks at 3:00hrs, just under 3:30hrs and under 4:00hrs as runners strive to record a sub-target time. Goal-setting is embedded in our current performance culture. We have school league tables, waiting time targets, in fact almost everything in our public life seems to be underpinned by targets. However, goals were not always so important. The phrase ‘goal pursuit’ was almost non-existent in English writing prior to 1950. ‘Perfectionism’ was virtually unused prior to the second quarter of the 19th Century. So-called management science and the pursuit of ‘efficiency’ means goals now infect almost every part of life. “Numbers pave the road to obsession”. Now we have ‘streaks’ – where we seek to maintain a continuous pattern of achievement. It might be running a certain distance in a certain time, or walking a minimum number of steps, building up a set amount of exercise each day, reading the bible, practising a musical instrument …. “Streaks expose a major flaw with goal pursuit: you spend far more time pursuing the goal than you do enjoying the fruits of your success.” There is only one near-certainty with a streak and that is that it will end.

Alter tackles ‘Feedback’. Children love feedback – leave anything with a button to press and a child will press it, just to see what happens. If their action has an interesting outcome – like a light comes on or a sound is made, then they will press again and again … It appears we adults love feedback too. The Facebook or Instagram ‘like’ button has shown how important feedback is to us. Feedback – plays a key part in the ‘Hook Model’ that underpins the primary addictive design patterns beloved of social media platforms, mobile games and casinos. Alter picks up on the themes of Human Behaviour modification – which also play a major part in this story. He quotes from the work of Natasha Dow Schüll, whose research has been into Casino practices, to illustrate some of the surreptitious tactics that used to provide ‘variable reward’ that lead to further ‘investment’, driving us to keep on playing. Alter also explores Virtual Reality (VR), “If idle smart phones and tablets draw us away from the real-world interactions, how will we fare in the face of VR devices?” “Why live in the real world with real, flawed people when you can live in a perfect world which feels just as real?”

“Irresistible” takes us through the importance of ‘progress’ and ‘escalation’ as key elements of creating addictive behaviour - particularly within gaming. This brings us back to the work of Professor Schüll and something she called ‘Ludic Loops’. Ludic Loops are the long-repeated cycles of activity, induced by carefully calculated and timed rewards that keep you playing. ‘Cliffhangers’ come next - the almost inescapable traps that catches us at the end of each episode in TV series and is kept for extreme effect at each season’s end.

Finally, we look at ‘social interaction’. Alter presents us with the comparative stories of Instagram and Hipstamatic exploring the relentless rise of one and the dramatic launch and ultimate demise of the other. Once again, the ‘hook model’ is deployed:

taking or airbrushing the perfect picture - action;

variable reward’ in the form of feedback;

investment – picking up our mobile devices and looking to see how many likes our pictures have; and

look at the pictures posted by people in our network, which provides the trigger to go and do it all again.

These same patterns are present in all social networks: Facebook, Twitter – and even for the business-people, LinkedIn. Alter and the practitioners he talks with see huge dangers in growing tendency for people to interact by preference digitally rather than face to face. They wonder whether the damage done in terms of loss of empathy and limited-bandwidth interactions can always be completely reversible.

The final section of the book addresses prognosis and solutions for behavioural addiction. Children (in the US … but the rest of the world isn’t so different) are spending a third of their life sleeping, a third at school and the remaining third interacting with various forms of media. More time is spent interaction with people digitally than face to face. Since 2000 levels of active play have dropped by over 20% and continue to fall.

Children are particularly susceptible to these technology-enabled addictive techniques as they have not developed adequately the mental means of self-control. This is a particular danger for children and young people who have uncontrolled access to addictive media.

There isn’t clear consensus on what is the ‘right’ way forward. Through different ages of development, advice seems to range from advocating complete avoidance (e.g. for 0-2 year olds from the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)), or rather more nuanced advice (from an organization called Zero to Three) which identifies different kinds of screen time, and is perhaps more concerned about the context of it than the access itself.

“Irresistible” introduced me to the concept of three striking (poor) parenting principles: “Scary, Crazy and Clueless”. These labels came from Catherine Steiner-Adair’s work interviewing thousands of teens and their parents. Scary parents, present rigid, judgemental intensity in their interactions dealing with digital challenges. Crazy parents overreact – adding drama to the sense of hurt, tending to put themselves at the centre rather than supporting the young person. Clueless parents are what it says – they simply don’t understand the context that young people are contending with – as a result there they to try too hard and repeatedly misunderstand. In contrast, Steiner-Adair advocates that parents should seek to be “Approachable, Calm, Informed and Realistic”. As parents of pre-teens we understand both sides of this problem too well; and part of the purpose of TechHuman’s work for families is to help parents to develop their understanding, overcome their fear and to develop realistic and relevant strategies for supporting their children as they navigate these tricky waters.

“Irresistible” acknowledges the difficulty of breaking old habits and making better ones. There is no set number of repetitions (or target streaks) that will represent that you have in fact overcome a bad habit or mastered a new one. We need to appreciate our uniqueness in all respects, including self-discipline and susceptibility to manipulation. One idea thinks make be helpful he calls ‘behavioral architecture’. This idea recognises that the physical arrangement of the space we inhabit has a material impact on the formation and adjustment of our habits. At its simplest - “Where is our mobile phone when we sleep?” “Where do we put it down when we return from work?” One of the challenges of our digital age is that it is almost impossible to be part of our society and avoid temptation all together. We can physically organise our live to put temptation a little further away. That will sometimes dull the siren call sufficiently to ease our discomfort. Alter explores all sorts of different ways this can be done and the potential value that pushing temptation a little further away (using apps that mask certain hooks e.g. the number of likes/comments etc. on a social media post). This offers an opportunity to dull the impact addictive technology has on our lives.

The final section of the book explores an important modern approach called ‘gamification’. In gamification, the designer takes a mundane or unpleasant task and finds ways to present incentives to the subject of the exercise to undertake that task, or to persist. It is a demonstrably powerful tool, that can materially adjust our behaviour. Just as with Nir Eyal, Alter is comfortable that manipulating our actions for ‘positive’ outcomes, justifies the use of these techniques. Shoshana Zuboff on the other hand would decry this behaviour as robbing us of our human freedom. I think we need a respectful debate around whether and when explicitly manipulative techniques can and should be used.

Alter reflects an instrumentalist view of the world; believing that technology is neither harmful nor beneficial of itself; that moral judgement can only follow when we examine the specific application of the technology. I personally struggle with that perspective – but again recognise that this is a topic which has not been part of an informed debate across society; perhaps one that would be worthwhile.

I learned a lot from this book and enjoyed reading it. I think it provides a helpful, broad overview of the nature of behavioural addiction in Society today, offering a solid foundation for his conclusions. Adam Alter offers us some pointers as to what we might be able to do about it.

© 2020 Jonathan Ebsworth